The Minesweeper SWERVE

The Minesweeper SWERVE

By Team Gravitazero

|

| Photo: US Naval Institute |

Playing the demanding game of wreck hunting is certainly exciting. Discovering new wrecks, researching their history, and reconstructing the conditions under which they sank all contribute to making wreck hunting an absorbing practice. However, at times, relationships with ex-crew members, the emotions called up by the human aspects of a wreck history, and other entwined events, overshadow the purely material aspects of the research.

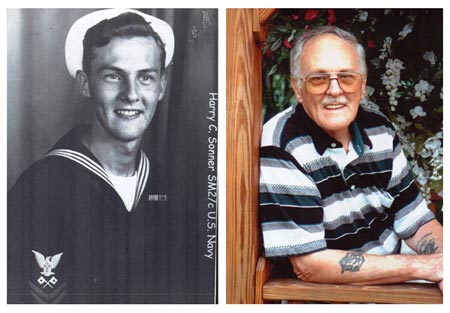

While researching the history of a wreck, one could be fortunate enough to find a survivor who was on board the vessel when it sank and who could provide one with a first-hand account of what happened; this happened to us. In our case, the survivor was signalman third class Harry Sonner. At the time of the sinking, he was no more than a boy; now 77 years old, his vivid memory still recalls the tragic events of World War II, a war which, among many others, cost the lives of thousands of young men during the Allied landings near Anzio. During the course of an extensive correspondence with Harry, a strong friendship grew between Harry and the members of Gravitazero, so Gravitazero wishes to dedicate this article to him.

On 10 July 1943, less than forty days after the Allied forces had occupied Sicily, the Allies quickly began to push northwards up the Italian peninsula. The occupation of the port of Naples was considered critical, but its success depended on controlling the southern beaches and coast. The invasion reached its most intense point during the bloody Allied landing at Salerno (Operation Avalanche), which cost the lives of more than 9,000 Allied soldiers.

OPERATION SHINGLE

Soon thereafter, the invasion stalled before the impregnable Gustav

Line, a German defensive line that divided Italy in two parts. The

cornerstone of this defense was the Cassino fortress. Faced with

this challenge, Allied headquarters decided that a diversion was

necessary, one that would allow them to hit the 14th German Army

Corps from behind. From this was born Operation Shingle.

D-day was fixed for 22 January 1944 at 0200. Assisted by one battleship group, two Infantry Divisions took part in the operation, one American and one English. The landing area was divided in two parts: Peter Beach, North of Anzio, where the English were to land, and X-Ray Beach, South of Anzio, which was to be assaulted by the Americans. The submarines HMS Uproar and HMS Ultor were sent on reconnaissance missions the day before the landings; the same night two minesweeper fleets began operations.

|

At midnight, 21 January, in the dark waters off the coast of the villages of Anzio and Nettuno, a force of 374 vessels of American, English, French, Polish and Greek nationalities gathered. On 22 January, more than 300 vehicles and 36,000 soldiers were rapidly deployed on the beaches, a force that increased to 69,000 in the following weeks. The Germans were caught, completely unprepared, and so the first phase of Operation Shingle was an unqualified success.

|

| Photo by Claudio Provenzani |

The German response was not slow in arriving, and over the next four months the whole area was host to bloody skirmishes. Only the fall of Cassino, between the 11th and 12th of May, enabled the Allied forces in the South to reunite with their beachhead forces. Reunited, they could then launch the attack north, towards Rome, on 4 June 1944.

|

| Photo by Claudio Provenzani |

To give an idea of the level of resistance encountered by the Allies, by the end of the battle of Anzio, the Allies counted 29,200 soldiers dead, missing or injured; the Axis forces counted 27,500 losses. During the landing and in the successive operations, twenty ships were lost.

MINESWEEPER OPERATIONS AND

SWERVE

“Where the fleet goes, we’ve been.” There is,

probably, no more eloquent phrase to describe the work of

minesweepers than this one. Every amphibious, military operation

must be preceded by, and associated with, a mine clearing

operation.

The same held true for Operation Shingle. Throughout the day before the landing, two fleets of minesweepers patrolled the waters off the landing beaches, working to create two safe channels for the landing forces. Many mined areas were left intact to act as a defense against possible sea attacks.

By 31 January, when the majority of the American minesweepers had left the area, a total of 34 mines had been removed over an area of 82 square miles. Despite the fact that on 4 June the Allied forces entered Rome, the deadly minesweeping work did not cease. Minesweeping continued until the 5 August and involved at least 2 AM Units and 6 YMS Units daily.

The first ship to be sunk in the waters off Anzio was a minesweeper, the USS Portent, and fate decreed that the last ship to be sunk in these waters would be one of her sister ships. On 9 July, the USS Swerve (AM 121) and the USS Seer received orders to clear mines from an area normally used by cargo ships, an area along the Laziale coast. At 0700 they left Naples, and by 1130 began clearing operations off the coast of Anzio. The USS Swerve was directing the operations. At 1259 its captain gave the order to recover gear and head back to port.

Harry Sonner remembers it very well: “ . . . I had just finished taking down a signal to our sister ship, USS Seer, to recover gear and proceed back to port, when an explosion occurred under our propellers. I saw all kinds of things flying into the air above me and thought, ‘The mast has to come down.’ So I headed for the pilothouse to avoid being struck. It was a good thing I did, because right where I was standing, above my head, a half inch steel cable wrapped itself around a speed hoist. I jumped off the signal bridge. When I hit the water and came up I looked up and saw the mast coming down on top of us. I started swimming to get away from it. It was all over in seven minutes from the time of the blast until the ship disappeared below the surface of the water. Our ship was gone . . . ”

The USS Swerve had seven injured and three killed. One of those killed is still aboard the vessel; the other two were seen killed by the initial explosion. The injured were taken to the hospital in Naples where they were given dry Army clothes and shoes, put on an Infantry Landing Craft, and taken to Oran in North Africa. From there they were taken back to the States. The USS Swerve received one battle star during her WWII service.

THE DIVE

We located the Swerve thanks to the help of Marco Bellosi, an

ex-deep sea diver who, after the war, together with his colleagues,

recovered the majority of metal from the wrecks in the Anzio area.

Using echo-sounding equipment, we eventually got a good signal,

indicating a large metallic structure rising up to 5 meters from

the bottom at a depth of 55 meters.

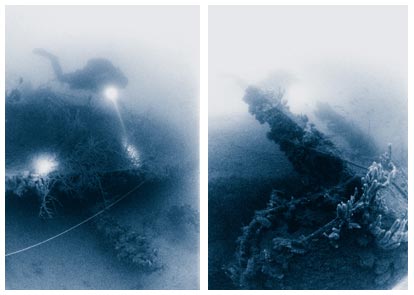

The following weekend, seeking to identify the remains of the above wreck as the Swerve, we prepared to dive. Marine conditions were reasonable but did not allow us to moor directly on the wreck. After several unsuccessful attempts to hook the wreck, we opted to use a buoy marker. When the gear was ready, the first team went into the water.

The buoy marker was positioned near the wreck, but, as usual, water conditions were bad. As the dive team began its descent, it found itself completely enveloped by a dense cloud of muddy suspension. Using a line, the team began to search in the direction in which the ship was thought to lie. Time, however, passed quickly, and it was only towards the end of its intended bottom time that the team managed to reach the side of the Swerve. There was just enough time to fix the line to the wreck, patrol the site to verify that the wreck lay, down on one side, almost covered by sediment, before they began their return voyage to the surface.

|

| Photo by Claudio Provenzani |

On the surface, the second team was ready to dive, and after a short briefing by the first team, it began its descent. The depth here was not extreme, but the presence of fishing nets, snagged by the hull over its fifty-eight years of residence on the seabed, made the dive difficult. The second team followed the line through the murky water until, finally, it saw the profile of the wreck materialize. Once it reached the wreck side the team began to cover it longitudinally. Poor visibility coupled with the minesweeper’s very poor condition rendered the wreck’s structures unrecognizable. Only after several dives on the Swerve were we able to give the correct position of the ship. She lies down on her port side with her bow pointing northwest.

The contact point of the second team was close to the aft of the ship; from there team members could discern only the saddle tank, several scuppers and a little crane, which would have been used to hoist and drop the minesweeping gear. En route to the bow, along the topside, the team was met by a lower deck air intake, then other big scuppers. Soon thereafter it arrived at the central zone of the wreck where large holes indicated areas cut out by deep-sea divers seeking to remove the engines.

Twisted metal plates rose up threateningly from the wreck; large

numbers of pipes and cables lay scattered on the seabed, as did

ammunition boxes half buried in the mud. Near the bow, a big cleat

separated two chocks and, beside these, the impressive navy stoklen

anchor was still held by its hawser.

In spite of her deteriorating condition, the ship serves as a

natural oasis for marine benthos. Her structures provide an ideal

habitat for filtering organisms such as sponges, gorgonians and

tunicates, and are completely covered by oysters and sea anemones.

These also provide shelter for many species of fish such as

congers, California scorpionfish, forckbeards, white seabreams and

European hakes.

A great deal of bottom time has been dedicated to the search for distinguishing characteristics that would lead to a positive identification of the ship. Towards that end, the total length of the hull was measured and photographs taken of the profile; these were then compared to a period print of the vessel. Deep-sea divers revealed an important clue about the identity of the wreck when they informed us that removing the engines had been easy because they were mounted on a spring system. This type of support was typical of minesweepers given that they had to be able to absorb the vibration caused by mine detonation.

References:

Samuel Eliot Morison. 1954. History of US Naval Operations in World

War II: Sicily-Salerno-Anzio. Vol. IX. Little Brown & Co.

Boston.

Arnold S. Scott. Most Dangerous Sea. A History of Mine Warfare and

an Account of US Navy Mine Warfare Operation During WWII and Korea.

US Naval Institute, Annapolis, Maryland.

Ennio Silvestri. The Long Road to Rome (Operation Shingle). Cipes

Ed.

Harry Sonner. USS Swerve AM 121. That fateful day. The Silent

Defenders, Spring 1999.

Giuseppe Tulli. Anzio: I Terribili Mesi Della Testa di Ponte. Anzio

Beachhead Research and Documentation Center.

Naval Historical Center. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting

Ships, volume 6.

Acknowledgements:

• Gravitazero would like to offer particular thanks to

“Anzio Beachhead Research and Documentation Center” and

their press agent, Amerigo Salvini, for their substantial

contribution of information on ships lost during Operation

Shingle.

• Marco Bellosi, Alberto and Ezio Ruberto for their help on

the search for, and identification of, the USS Swerve. Naval

Historical Center, Washington Underwater Archaeology Branch.

• Naval Mine Warfare Association and their Vice President Kris

Gretzinger and Historian Joseph F. Schreiber Jr. for their help in

finding USS Swerve survivors and the material on minesweeping

operations at Anzio and during WWII.

• Alessandro Fornair and Cristina Nicolai for boat support and

assistance during decompression.

• Nick Connell and Marcella Pesce for translation

assistance.

Copyright ©2002 Global

Underwater Explorers.

All rights reserved.